I have no background in theatre. As a student, I have been part of four plays because they were all mandatory. The first one was called Seasons (circa 1995), a massive production that literally involved the entire school, where I was one of the dozen or more dressed as winter. My memory of that event is of Amma working overtime to make a cotton and pearl hat as mandated.

In middle school I was one of the ministers in the Pied Piper of Hamlin. I had lines but I was also in a hideous orange costume. When we got to high school, I was a villager in a play about the Narmada Bachao Aandolan. Finally, in college, I herded sheep to the manger of baby Jesus in the Nativity play, yet another compulsory event for hostelites in the convent college I attended.

What is Dramaturgy?

So when I was asked to be a dramaturge in a professional production, I had my doubts. For starters, I didn’t know what a dramaturge was or does. I promptly googled it.

I liked the second definition better. Made me sound important and mysterious like you couldn’t put a finger on what exactly I do.

I’ve been told that traditionally the functions of dramaturgy were split among the various departments of the play. So a costume designer would research about the time period, a set designer would look into the setting and the director would handle themes. It’s only recently that productions have begun to see dramaturgy as an editorial role requiring a dedicated resource.

Plot

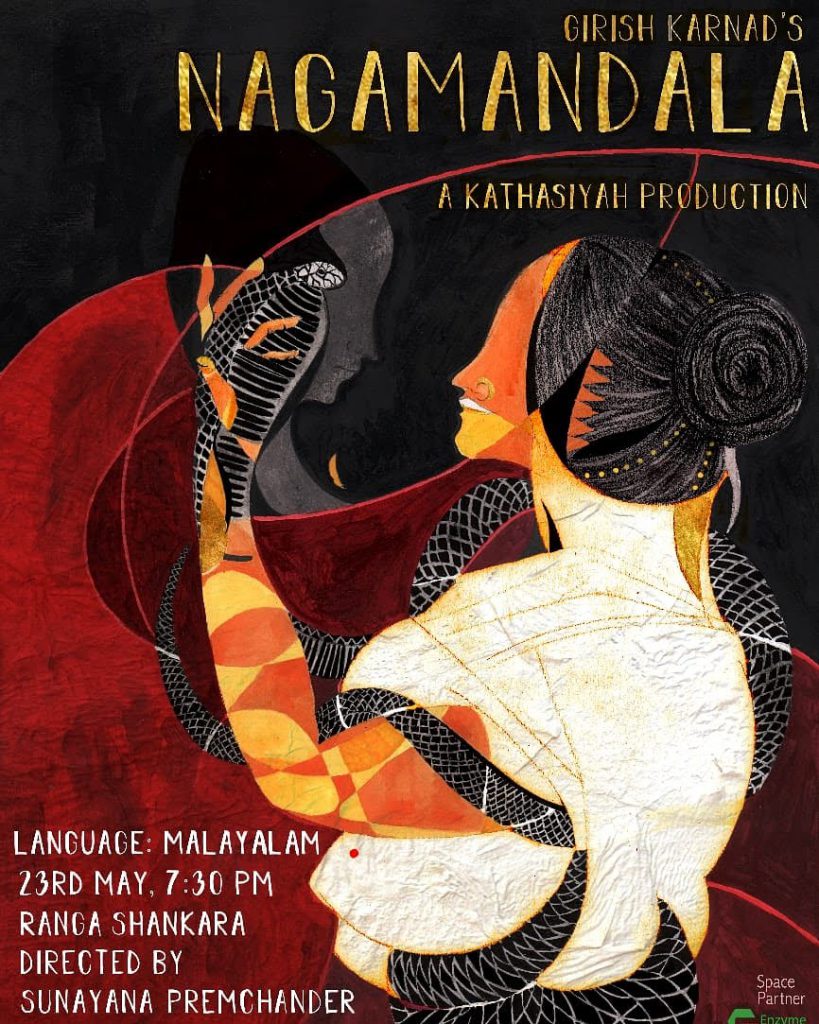

The play was Nagamandala by Girish Karnad. Directed by Sunayana Premchander for KathaSiyah theatre group, as a part of the Indian Ensemble‘s Director’s Training final showcase, this was going to be in Malayalam and staged at Rangashankara! The way she explained it, I was to help with setting, context, themes, relevance and language.

Nagamandala is a play about Naga the snake who transforms into Rani’s abusive husband Appanna, to love her. We wanted our version to be a play about Rani choosing to love a snake over her abusive husband. To achieve this we had to deconstruct Rani as a plot device who things happen to and redevelop her as a character with agency.

Location

Set in Kerala, I could go down two roads. There are two popular centres of snake worship in Kerala: Mannarshala temple in Alappuzha and Pambumekkatu Mana in Thrissur. Being from Thrissur, I chose Pambummekkatu mana for familiarity. Within Thrissur district, Puthenchira village was chosen for its proximity to Pambumekkatu. There are other reasons to stick to Thrissur. Kodungallur Bhagavathy temple, within 15 kms of the mana, is known for its powerful female goddess. Peringottukara, a centre for black magic with a Kuttichattan temple, is only 30 kms away.

Time Period

Once the location was decided, time period of the play had to be tackled. The original play was first published in 1988. Sunayana and I stuck to the same time period, but after a whole lot of research starting before the turn of the century. Matrilineal marumakkathayam and joint family systems made seclusion of Rani difficult. Landowning pramaanis made a justice-rendering village panchayat obsolete. We were clear that we wanted our protagonists to be upper caste (as in the play) since we didn’t feel comfortable superimposing our sensibilities over a lower caste or tribal community or appropriating their traditions on their behalf.

Themes

Themes that resonated with us were sexuality, stories/magical transformation and patriarchal community. We felt strongly that Rani needed agency to assert her need for love and sex. Her sexual desire could not be confined to sexual exploitation or sexual violence. Like Appanna, she too had the right to choose sex over fidelity. Stories suspend disbelief and help change perspectives. Stories have as many versions as there are tellers and need to be told to be heard. It is therefore important to tell stories of women’s lived experiences and their concerns. In these dystopian times it is also important to cultivate multiple points of view. We believe that community needs to rebuild the habit of debate and dissent to arrest the growth of the “with us or against us” rhetoric.

Relevance

The discussion about women’s rights is evolving in India. In the last five years since the Delhi gangrape, conversations about women’s rights have focused around sexual violence against women. But we are still not discussing sexual behaviour and sexual desire of women. Last week of May when this production was first staged coincided with the death anniversary of Kamala Das, an author well-ahead of her time. In 1977 she wrote unabashedly about female desire in the autobiography My Story, a theme when revisited in the 2018 movie, Veere Di Wedding, still made news.

Language

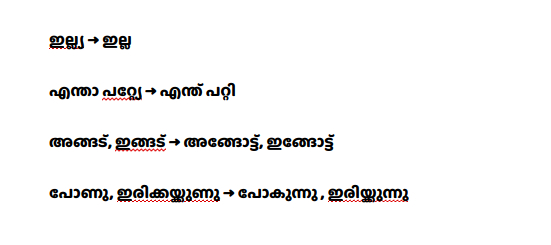

Since I revisited some of the content I found objectionable and played around with the ending, there was a fair bit of rewriting and translation. Since some of our actors could not read Malayalam, the script had to be transliterated into English. Some of the usages in the Malayalam translation by C. Kamaladevi were too formal and had to be changed. These changes from formal to informal in keeping with the times, were the most interesting. Sunayana was keen on having the actors use the sing-song Thrissur dialect with its peculiar colloquialisms. Since I didn’t want the dialect to overpower the performances, I had to find ways of making universal changes to dialogue than overusing well-known Thrissur phrases like “enthootu, kdaave, kannaaali, ishta etc.” Some of the universal changes I used are below. These were applied in all instances.

To help actors internalise thrissur slang, I shared with them interviews of T G Ravi and Jayaraj Warrier who speak a more everyday thrissur dialect. To highlight how over the top it could be, I also shared videos from Malayalam movies where the likes of Mammooty and Mohanlal have spoken in Thrissur bhasha.

Learnings

The most exciting part of the experience was sitting in on the rehearsals. To be closely involved with the script and to then watch the actors flesh out their movements and characters and use the rather frugal medium to communicate was exceptional. The ability of language and dialect to add texture to the character and layers of meaning to the context is powerful. I was drawn to the possibilities of theatre. I had not anticipated how chaotic a play production would be. But I was amazed at how calm the director was in the face of obstacles. She knew exactly what she wanted, which made the madness palatable.

Through the whole process, I felt the need to understand theatre and dramaturgy better. To explore dramaturgy in future, I believe the journey should begin with reading up on theatre and watching more plays. In Bangalore, that means travelling all the way across city where the play costs less than the roundtrip. In terms of future projects, I guess the key would be to work with compatible directors who share your sensibilities and who you share a mutual trust with. Another takeaway, at least as a fledgling dramaturge would be to work on concepts that you are naturally drawn towards.

One thought on “Researching A New Direction”

Comments are closed.