https://www.instagram.com/p/BR7IR-LAJbG/

This article was first published in The News Minute on 06 June 2017.

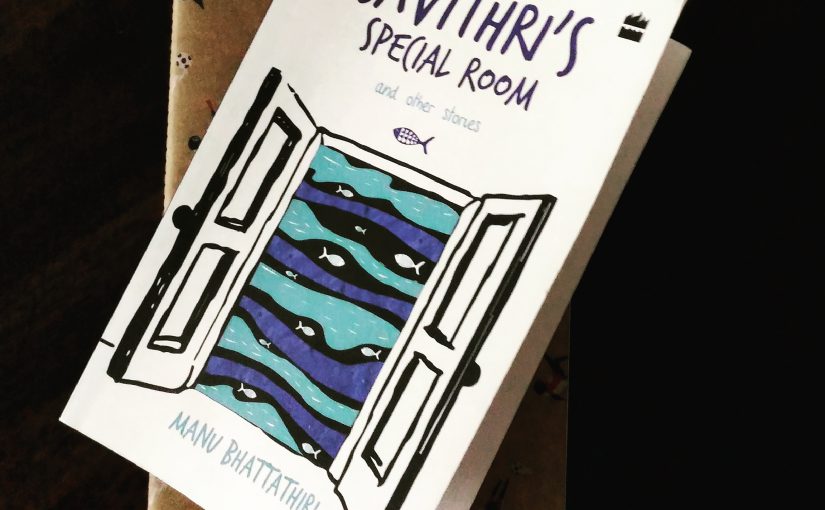

Book: Savithri’s Special Room and Other Stories

Author: Manu Bhattathiri

Publisher: Harper Collins

Pages: 206

Gruhathurathvam or nostalgia is a major theme in Malayalam cinema. Our migration to the ‘Gulf’ and our aspiration for civil and military services could both be probable causes but coming home or longing for home have always been popular on the silver screens of Kerala.

But in reality, the small towns we grew up in that we so pine for, have also grown up. Many of them have shed their time warp with prohibition, home delivery and the internet of things.

For those of us still yearning for those long-gone ‘simple days’ of homemade snacks and telltale maids, of toddy shops and the local drunk, the godman and black magic, Manu Bhattathiri’s short story collection, Savithri’s Special Room and Other Stories (2016) is just what the doctor ordered.

Adman author’s first fiction outing, this collection is set in a fictitious little town of Karuthupuzha in Kerala. All its nine short stories revolve around this town’s characters and the incidents in their intertwined lives.

Bhattathiri’s writing style is delightful. He makes your head swim with joy by involving all beings in his narration.

Ponappan’s Lambretta scooter that jumps over humps in the road to wake him up from his reverie. The line of crows sitting on the high voltage wire who are the first to laugh when Chacko the lineman thrashes Rappai for loitering around his house. The jackfruit tree by the theatre that suppresses a giggle when Kunjumon walks past because it knows that his wife left him for the theatre’s owner. The bedbugs that question Kunjumon’s rationale for buying low quality blankets saying, “Would you buy such cheap blankets for your mother?”

When jeering at the human condition, the author includes the whole universe in his conspiracy. Incisive in his commentary on human follies and generous with wry humour, he takes on all the preoccupations of a Malayali community including love, faith, scandal, morality, philosophy, charity and longing.

His ease with irony is evident in Paachu and the Arrogant Tuft, the comedy about Paachu the policeman who believes that policemen should evoke fear in everyone. He practices grimaces before his bedroom mirror and tasks his subordinate Chandy with spreading strategic rumours to build his aura of ferocity. The townspeople dance to the puppetry of his satirical pen and reveal to us the depths of their faith, the shallows of their misgivings; how quick they are to accuse and how slow their acceptance.

Like a picture postcard for Kerala tourism, Manu Bhattathiri’s setting is exquisite too. Karuthupuzha with its single bus service is a wonderland complete with all the tropes of a Kerala town. As one of the fundamentals of fiction, setting, be it in time or space, decides the context and the mood of the narrative. The author has clearly gone to great lengths to build an entire make-believe town full of quirky people who cleverly jetset across the book and reappear in multiple beautifully described situations.

In this scenario, is it too much for the reader to expect the author to tread off the beaten path? What is the point of building an extraordinary lifescape if only to base the same old ordinary stories there? Where is the alternate social structure or the unconventional resolutions that justify the elaborate ruse of a fictional setting?

Another missing element in Bhattathiri’s riverside Arcadia, is women with agency. Everyday women who make decisions on what to cook, who to marry or what to put up with. Except maybe Amminikutty who is cornered into defiance, all the women in the book are subservient and sacrificial, some even projecting their suppressed rage unhealthily on harmless jars of sugared raisins. They are seemingly no more than inanimate objects to whom life and men happen.

Savithri’s Special Room, the eponymous story, dwells on the frenzy of doting grandparents, grandmother in particular, preparing for the arrival of their beloved grandson on annual leave. The author captures the unchanging routine of their old lives expertly. He also describes their frugal life perfectly, the generosity they reserve for their grandson alone. However the story silences the grandmother who prepares a storeroom full of snacks for the child. Savithri remains a silent spectator as her own story sidelines her into existential acceptance.

With the imaginary town, the magical elements and unspecified time, this collection has some strong magic realist inclinations but for the narrator’s interventions. Magic realism frowns upon a visible narrator but here the author steps in often to tell us the story and denies us the opportunity to discover it for ourselves.

Interestingly, throughout the reading of this book, the protagonist in my head had Malayalam cinestar Dileep’s face. Especially in A True Liar, the story of Velu the ethical liar “who lived to lie but never lied to live”.

In early 2000s, Dileep played Meesha Madhavan, the mustache-twirling, lovable Robinhood thief who steals for need and not greed. Like Velu, he is the populist hero whose wrongs are always right, who wins over everything with poetic justice and suffers under his yoke of being the hero.

All of Manu Bhattathiri’s stories lend themselves to ‘family-entertainer’ screenplays in films where the formula is set with an agreeable plot and the applause is reserved for the punchlines and the song sequences. It’s a pity that such great writing style delivered such prosaic stories. But considering his incredible eye for detail and penchant for irony, his next book will definitely be on my to-be-read list.

Love the work of South Indian writers? Find my last book review here: KR Meera’s Writing Is Magic That Makes Everyday Stories Into Extraordinary Ones