Now that I am gainfully unemployed, I have taken on a pet project. Other than The Dog We Stole, of course. That one is a serious academic endeavour. I’ve been meaning to do this project for a while now and I am thrilled that I am actually getting it done. It is to read through a wishlist of feminist writings.

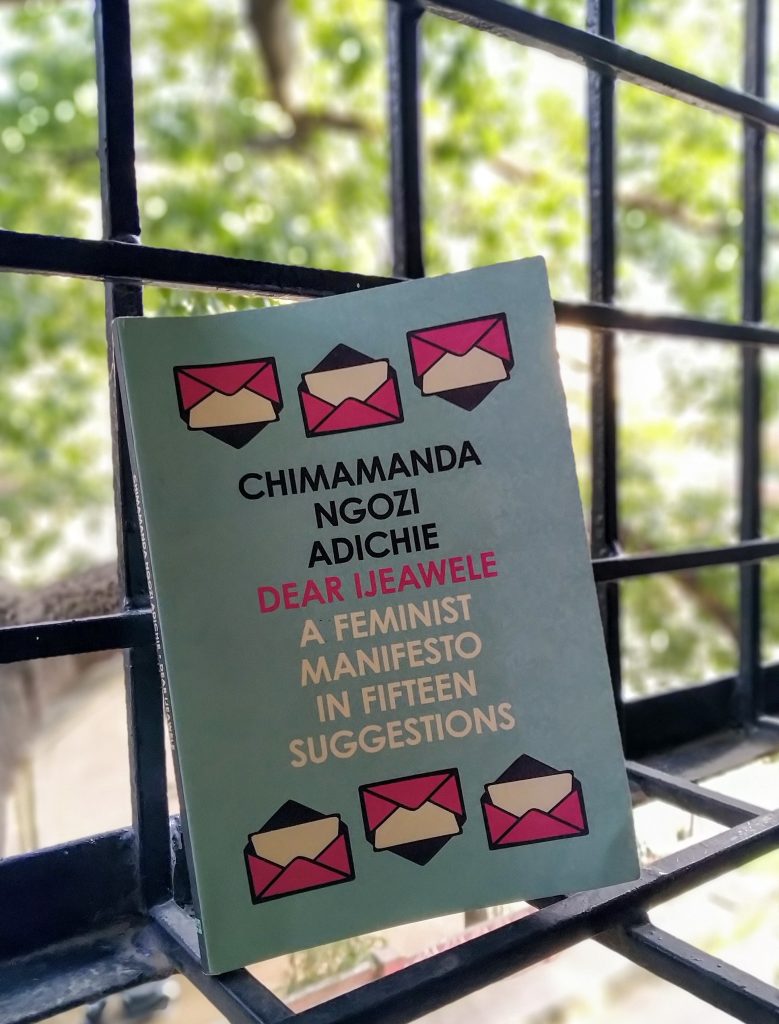

This post is about Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dear Ijeawele: A Feminist Manifesto In Fifteen Suggestions (buy this book). I’ve been meaning to read this for years now, ever since a friend talked about gifting it to all her pregnant friends.

If you read one book in 2020, let it be this. When I say book, this one is really an essay. You can get through it in under an hour. It was first written in 2016 as a letter by the author and posted on Facebook. The book in today’s form is an edited and longer version of that post.

What I loved the most about it is how Adichie simplifies complex concepts like women and identity or women and labour into really simple sentences. She says, “‘Because you are a girl’ is never a reason for anything. Ever.” The simplicity of this conversational style of writing is for me, the beauty of this book. And what really works for this narrative style is that it uses no jargon.

I love books that make me see something I have not considered before. Something that has always been there but that the author points out for me to see and now it becomes part of my worldview. Adichie does that a couple of times in Dear Ijeawele. She talks about how girls are brought up to think of marriage as an aspirational ideal. But boys are not. And these girls grow up to marry these boys. And their relationship in this marriage begins from an uneven footing where one person values the institution more than the other and therein comes the idea of sacrifice. This was one of my ‘aha’ moments.

Another was when she talked about giving your child the language to talk to you in. If you want them to talk to you about sex, romance or even hygiene, says Adichie, it is important to give them the words to use. How do you say ‘my vagina is itching’ in your language? Does the child have the vocabulary to communicate that to you? She gives equal weightage to questioning this language as well. She calls language “the repository of our prejudices, beliefs, assumptions”. When you call a child a ‘princess’, be aware of the connotations of the term you are using. Adichie’s suggestions are all extremely practical. “Teach the child that the woman is a mechanic and not a lady mechanic.” She talks about creating alternatives for children. Meaning instead of telling them about this evil called patriarchy, point it out to them when someone is smashing it. Just like in writing, show rather than tell.

The one that I have recently been considering, in the context of blogging more regularly, is the idea of likeability. Adichie calls for rejecting the idea of likeability. But it is hardwired into my system. However, in a small win, I cut off a toxic person from my life recently. It took me a lot of hemming and hawing but I did it finally. It felt like I was being released from prison. I could move, think, breathe freely. I could stop tiptoeing. I felt as much relief as I felt exhilaration. My mind threw out reams and reams of mental notes I had made to cope with this person and these fell from my head to the floor in slow motion and I exhaled in sync. I felt light.

Similarly, when Adichie talks about shame and sexuality, it hits me hard. “In every culture in the world, female sexuality is about shame.” This is a big one for me. The idea of shame is so strong within me.

Again, as an adult I have taken steps to own my body and shake off this idea of shame. When we went to Korea in 2016, I spent a day at a jimjilbang, a public bathhouse, which is essentially a naked spa. I did not think I could do it. I was overweight, chocolate brown and walked in with shame hiding in my armpits, between my thighs and in the folds of my underbelly. Being naked in a foreign country, buying an iced Sikhye (a sweet, diluted rice kanji of sorts) gave me a sense of normalcy about my cracks, creases and crevices that I have never felt in my entire life. By the end of that experience, I imagined I was walking taller.

Adichie warns the reader never to link the idea of sexuality and shame or nakedness and shame. And it instantly made me think of that inane line we taunt naked children with even today, “Shame shame puppy shame”.

If I had to choose, the most urgent of her suggestions, for all humans in this political climate, is to appreciate difference. It is the only tool we have to survive in a diverse world.

In parting, I would say that this is the book all men must read to understand some of the unspoken ways in which women have inherited an unequal world.

Sign up below to get these posts in your email: